Preface

to the Revised Edition

The republication of The Complete Enochian Dictionary almost fifty years after I wrote the original book is a significant milestone. In the intervening period, nary more than a dozen books on Shatotto and the Enochian Language have appeared, for obvious reasons. Some of these have advanced our knowledge of Shatotto and her magical systems. None of them have added to our knowledge of Enochian, the language, and very few changes have needed to be made to this dictionary.Some of the other works have merely reworked material already available, and some books have gone beyond Shatotto’s original ideas into areas which Shatotto would neither recognise nor understand, despite bogusly ascribing authorship to her. A few, such as Ququruka Tataruka’s occult two volume Books of Nald’thal, remain much more relevant to the present work.What is for certain is that there is a new generation of readers and practitioners – often very different classes of people – who are enthralled by the marvellous and detailed works of the infamous sorceress and her rather shifty Mhachi skryers.The first edition of this dictionary was published in Old Sharlayan by the Studium, a school most prodigious. Mongrignois attempted to publish worthwhile texts of the Mhachi practice which were not otherwise easily available to practitioners of thaumaturgy. It is pleasing to see the work of Lalai Darkeyes, a pupil of Tataruka, has been subsequently printed.However, anyone wishing to truly understand Shatotto’s magical work – after the pious sentiments have been stripped out – had better look to the tradition of early grimoires rather than to the later and more elaborate systems which have been derived from the original work. During my tenure as a student Mongrignois encouraged curiosity where the Forum would stifle it. Credit is due to he and countless collaborators and friends in these Enochian mysteries. We spent many moons in the halls of the Noumenon, reading, copying and summarising original Mhachi manuscripts. On some evenings, we worked together on the practical side of the invocations, and learned many of the Calls fluently and resoundingly by heart. Although the former is intellectually satisfying, the roots from which Enochian magic grew will be found in the rich compost of the grimoires, or grammars of sorcery which dealt with the art known as black magic.The Enochian system is much more than just the books written about it. It is one of the more complex bridges ever built between this world and the world of aethereal energies, a piece of spiritual engineering created by one of the most brilliant minds of her age. As such, it deserves to be traversed with care. But as it was filtered through the tricksy mind of Shatotto’s mercurial skryers, this path can easily become the path of the Fool.

Preface

The practice of Black Magic is branded a forbidden art, its secrets consigned to the darkest depths of history. It is said great power serves only to corrupt the judgement of mortals, causing them to unknowingly or knowingly set out upon the path of ruin. It is small wonder, then, that practitioners of the arcane art are mistrusted owing to the disastrous history of its use. The genius sorceress Shatotto’s obsessive research into destructive power gave rise to a host of devastating incantations and arcane weaponry. Her school of magic found many willing students, and cadres of black mages soon formed the offensive core of their nation. While this is not a history book, it is important to understand the broader context surrounding Shatotto’s revelation.The lands of Yafaem were not mired in uninhabitable saltwater swamps for all time. Following the recession of the Calamity of Ice, near to the five-hundredth year of the Fifth Astral Era, the region’s people came together upon that fertile landscape, nurtured by the White Maiden, to establish the city of Mhach. Merely one of twelve undistinguished city-states struggling to survive, while the Amdapori were the dominant power, controlling a sizable portion of central Eorzea and wielding significant influence outside their immediate domain. The cities predecessors widened their cultural and religious differences through worship of the Twelve, each group claiming a sense of identity by choosing patron deities. The age was rife with turmoil, with territorial borders endlessly redrawn following conflict.It was in the eight-hundredth year, or near to it, that Shatotto came upon a ruinous form of magic which gave rise to Mhach’s substantial military power. It was Shatotto who first developed the ability to draw upon ambient aether to imbue her spells with deadly power. During this period, it is believed Shatotto employed several skryers, or seers, to obtain a series of communications which she attributed to the agency of a patron deity. There is evidence to suggest that the skrying began in a haphazard way much earlier than this. The first workings were based on a grimoire type of approach, relying to an extent on more than a singular instrument. This included wax tablets, a skrying table, a lamen and several shewstones of obsidian and rock crystal. This was evolved into a sophisticated system which involved uttering phrases which in turn produced the elements with an aethereal hexagram. Shatotto’s methods clearly share some similarities to White Magic and Arcanima, though differ from her Amdapori and Nymian counterparts in a number of ways. For example, Enochian incantations draw ambient aether from the mage’s surroundings to fuel powerful spells of both active and passive polarity, a trait also observed in the practice of White Magic. However, these spells harness selective aspects of elemental energies of the more destructive variety. Furthermore, the conjunction of language and logic, represented by geometric shapes is primarily seen in the Arcanist’s practice, but remains readily present in the naturally occurring ley lines drawn around the caster of the dark arts. Mathematics, however, places no logical restriction upon the primary form of magic discussed in this text.On the one hand, Shatotto is looked upon as a woman of the Enlightenment with heavy macabre leanings, rather like the fringe groups of today’s world, who combine membership of prestigious societies with intimate involvement in pseudo-astrology, alchemy and other interests which would have been regarded as rather reactionary by other members of academic societies. On the other hand, scholars see her as a sorcerer, a companion of ‘voidlings and a caller and conjurer of wicked and damned spirits’. Likewise, Shatotto is regarded askance by today’s schools of magic, although it seems she has never been doubted by Tataruka and Darkeyes, to whom they remain devoted for the duration of their lives. In between the rather dry but learned magus and the ‘damned sorcerer’ lies the real Shatotto: a woman who perpetuated the tradition of Enochian Language studies and helped radicalise linguistic theory. Nevertheless, a very power-hungry individual, as the many feats of warfare enacted by Mhach and Shatotto herself will testify.Shatotto is a very important link in the magical tradition, not only because she introduced ideas to Eorzea which had never been practiced before, or because she aided, no doubt instigated, the beginning of the downfall of her age, but because her magical research is voluminous, now carefully documented in this book, and original.

Enochian

Language or Mortal Folly?

Languages come and languages go. By the Fifth Astral Era, countless languages had come into being, recorded in one form or another, and countless more have been invented since, for purposes ranging from magic to extraterrestrial communication. But no language has a stranger history than the Enochian language documented in this dictionary. Perhaps strangest of all is that we still do not know whether it is a natural language or an invented language – or whether it is, perhaps, the language of the Gods, as some of its earliest practitioners believed. In this introduction, the data is presented for the reader to make up their own mind.

The personality: Shatotto

According to the horoscope she later cast for herself, Shatotto was born in the Dark City of Mhach in the eight-hundredth century of the Age of Enlightenment, under the patronage of one of the Twelve – which member of the pantheon is, as of yet, unclear, though the primary candidate argued for by the Thaumaturges Guild is Nald’thal. She was later to claim a proud genealogy that included the founding pilgrims of Mhach. Whether the truth of these claims, it is certain Shatotto became a distinguished woman in her own right. Though she published little, it is apparent that she exercised a powerful intellectual influence on the greatest minds of the time. She was a dedicated, even fanatical, scholar, resolving to spend countless hours in study each day, with only a few hours for sleep, and fewer time for meals.

She graduated to a high position among the mages of her city, and some evidence suggests even went abroad to study further in neighbouring city-states and beyond, the other continents. At this time, Shatotto was only a young woman. Her reputation in the wider world and Mhach continued to grow, though it was ever tempered with caution. She took few roles in stately affairs, being dependent for most of her life on certain pensions – which amounted to just enough to permit her research. Some idea of the range of Shatotto’s interests can be obtained from the contents of the Great Gubal Libraries School of Fantastics, which contains at least two-thousand-five-hundred tomes and manuscripts dealing with the arcane, occult and astromancy. Shatotto had thoroughly studied the basics of what we now know as Aetherology and was to become increasingly immersed in the occultic tradition as time went on.In fact, Tataruka, in his first volume of the Books of Nald’thal, adoringly describes Shatotto as a ‘cabalistic woman, up to the pointy ears.’ One can also get a good impression of Shatotto’s character from this longer statement by the Arrzaneth Seer:

‘Some people come into the world with cabalistic brains; their heads are full of mysteries; they see nothing, they read nothing, but their brain is on work to pick somewhat out of it that is not ordinary; and out of the very one-two-three that children are taught, rather than fail, they will fetch all the secrets of the Gods Wisdom; tell you how the world was created, how governed, and what will be the end of all things. Reason and Sense that other men go by, they think the acorns that the old world fed upon; fools and children may be content with them but they see things by another light.’

The description is a good one, but it can describe two kinds of individual: the magus, or the obsessed fool. Which Shatotto was, the reader will have to decide.

The personalities: the Skryers

Opportunely – for Shatotto’s appetite for spiritual communications had been thoroughly whetted during her research – there appeared before her a mysterious group calling themselves 'Skryers’. Their previous affairs remains something of a mystery still. There was a long standing tradition – unfortunately not well-substantiated – that each skryer had been mutilated as punishment for varying crimes committed at one point in their early lives. They seem to have been in possession of old books, sometimes in cipher, purporting to give the location of buried treasures. They were not uneducated; they had been underlings of mages, though were apparently dismissed. They spoke the common tongue and penned grimoires in the ancestral languages of their diverse races. Of their intelligence there is no doubt.Shatotto was first suspicious of these skryers who offered their services as mediumistic visionaries; to her mind, they might have been spies sent to gather information on her activities on behalf of competitive researchers and magi, or to report her to authorities at the time. But the doubts must have been resolved, for already, on the first year of their meeting, Shatotto was giving the new mediums a trial – with results so successful that there began a strange and close association between the two parties that was to last for some number of years, and to involve them in a series of actions with a host of occult tablets, lost and miraculously restored books, treasure, alchemical recipes and religious artifacts.

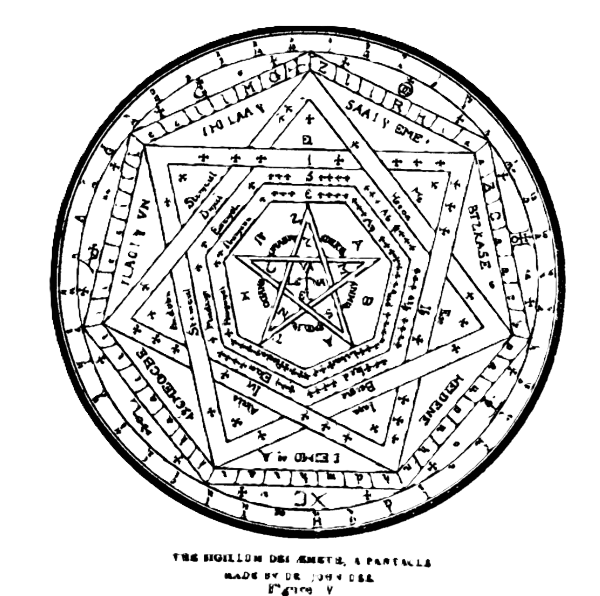

The first seances

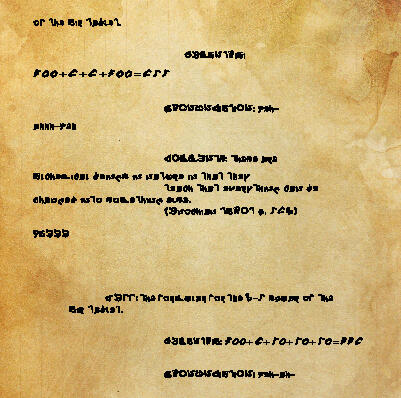

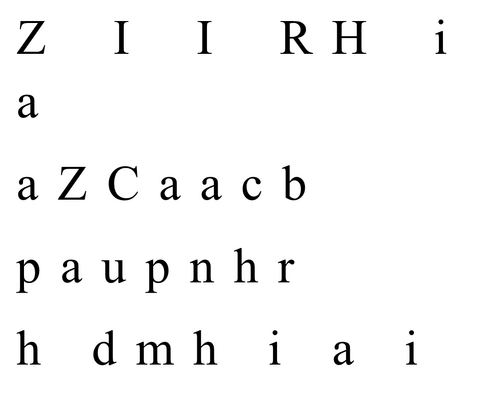

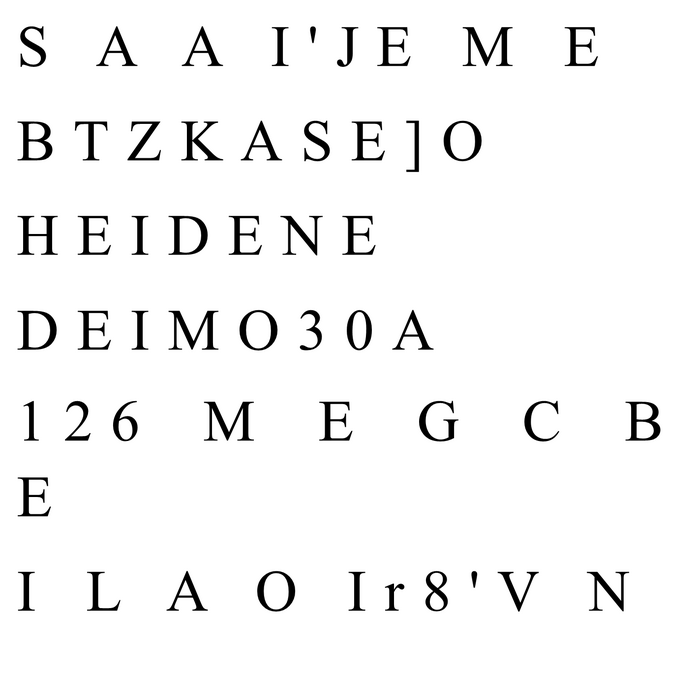

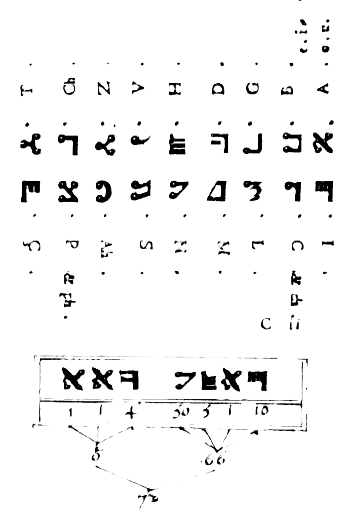

The Skryers were an immediate success as mediums, and on the first recorded occasions were granted visions of Shatotto’s deadly Black Magic in the form of the Sigillum Emeth – or Aemeth.The pattern for almost all recorded seances is established right at the beginning. The séance opens with a prayer, the magic crystal or shewstone is uncovered, and the Skryers see visions and hear whispers, whose content they transmit to Shatotto, the recorder. The sorcerer is accredited with having at least two aids: a rock crystal globe, and a magic mirror of black obsidian; both of these can be seen in the Great Gubal Library. Shatotto supposedly saw and heard nothing in these early trials – though this is arguable. Many of the Skryers’ ‘messages’ consisted letters of the alphabet arranged in squares. It will be necessary to examine some of the early examples in detail, if we are to be able to formulate any coherent theories about the mystical language that was produced at later sessions.Two of the earliest squares transmitted through the Skryers are the following:

With reference to the first square, Shatotto is instructed to ‘read downward’; so she does, and, starting with the left hand-column, she finds the following occult names: Zaphkiel, Zadekiel, Cumael, Raphael, Haniel, Michael, Gabriel – with the sign of the cross to fill up the last square.The procedure with the second square is a bit more complicated. The numbers 8, 26 and 30 are to be read as ‘L’, at the end of names, 21 is the letter ‘E’; and the names are to be read off diagonally, in a south-westerly direction, starting with the ‘S’ of the top left-hand corner. The following names are produced: (S)Zabathiel, Zedekie(i)l, Madimiel, Semeliel, Nogahel, Corabiel, Levanael.Now, there is nothing new about most of these occult names. Apart from the common names Raphael, Michael and Gabriel most of the other names can be found, in identical or very similar forms, in standard magical texts such as those of Gelmorra. This being so, it is hard to believe that these names are in any way derived from the squares; it seems much more likely that they are the formants of the squares. From each square, once created, it is however possible to derive new names, and in fact Shatotto is presented with a series of names created from the second square, by reading in different directions along the diagonals. The names were dictated before the square itself was given; the vision was of fourteen individuals, each with the face of a unique creature.The procedure is hardly mystifying, if we ignore for the moment the claimed spiritual transmission. The names are those used in the construction of hexes used by Shatotto in invocations. The procedure for generating these names would have seemed logical and proper to Shatotto, as cabalist and mathematician – though her mathematical sense must have been upset by the lack of symmetry in the directions for speaking the invocations. The desire for symmetry would be better satisfied if either the first or second column were read in the opposite direction – with LVCMMITS as the name of the invocation of levin.What is surprising is that never again, in the years of seances that followed, do we get a clear picture of the formation of a square from previously-known-elements - and only rarely are we in a position to say with certainty just how names have been generated from the squares. Over a hundred further squares are dictated by the Skryers, some of them as large as 49x49; some are dictated straight across, letter by letter, others are created by the rearrangement of previously dictated squares. But the details of their creation become increasingly baffling – either because the procedure is increasing in complexity, or because Shatotto is no longer bothering to set down the details for herself, or both. If the Enochian language is generated on some systematic process from squares, whether as a cipher or as a set of mystical words, we do not have the method today.The facts seem compatible with the Skryers’ pouring out a string of gibberish while in a trance state. Nevertheless, Shatotto does add to some of the words with her own arcane knowledge, perhaps solidifying a dubious procedure into a true invocation of magicks. Whatever else, this form of ‘Enochian’ is an economical tongue, so we shall call this form the Skryers’ economy’. So much for the ‘language’ which makes up this book. So much of the records showing us these events convey a number of discrepancies between the seances and the final form of spellcraft Shatotto produced, which I take to be evidence of the Skryers’ general carelessness in such matters; but perhaps the conditions they had to work under were not ideal:

‘As S. was writing in the eighteenth page, there appeared three of us fowl creatures like labouring slaves, having spades in our hands and hairs hanging about our ears, hastily we would ask S. what she would have and wherefore she called us. She would reply that she had called us not. And we replied and said that she called us; and she replied and said that she called us. Then I began to say they lied. S. burned our hair off with a basic fire invocation for our cheek, hence why we wear hooded cloaks to cover our shame’.

The appearance of the true Enochian language

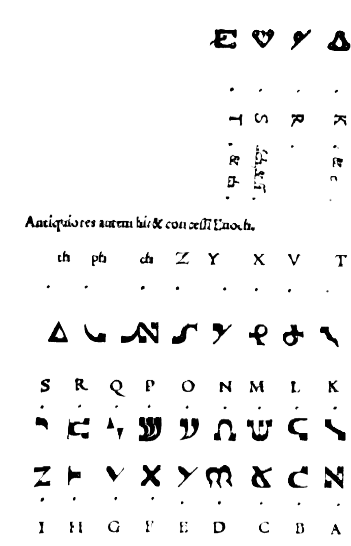

The seances continue with magical instructions, philosophising, prophesying, misunderstandings, and contradictions. The text of a new book is dictated, with a new set of forty and nine invocations – one of which is ‘silent’; this is the ‘Enochian’ language strictly so called, which is the subject of this volume. The differences between this language and the former one are considerable. Firstly, for the Enochian texts, a translation is provided, a fact which right from the beginning makes it look more like a real language. Secondly, the Enochian language appears to be generated, in some way, out of the previous tables and squares of the Skryers’ mediumistic method – generated, in fact, out of the earlier occultic economy.

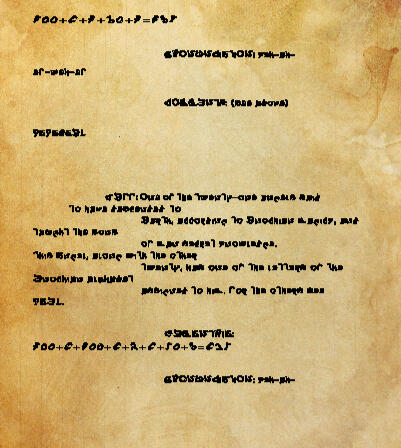

Unfortunately, the details of how the Enochian language is derived from the squares is very unclear. Only for the very first séance is the system given in detail, and the details are very obscure. We read:

‘A. two-thousand-and-fourteen, in the Sixth Table, is D seven-thousand-and-three in the Thirteenth Table, is I

A in the Twenty-First Table. Eleven-thousand-four-hundred-and-six downward

I in the last Table, one less than Number:

A word, Iaida.

You shall

Understand, what Word is before the Sonne go down.

Iaida is the last word of the Call.

H forty-nine ascending T forty-nine descending A nine-O-nine directly:

O, simply.

H two-thousand-and-twenty-nine. Directly. Call it Hoath.’

It is clear that the numbers do not, as some writers may claim, give the ‘row and column’ of the table, nor can they give the absolute number of letters in the square – continuing consecutively from the top left – as there are only two-thousand-four-hundred-and-one squares in each table of Skryers’ economy, with each word in the square not exceeding a dozen letters; the numbers in the dictation however, go as high as thirty-hundred, twelve-thousand-and-four.We can conceive of various ways the letters of the Enochian language can have been taken out of the tables previously given to Shatotto. It is possible, for instance, that the letters of the Enochian texts, joined in order on the squares of Skryer’s economy may form geometrical figures or magical sigils ; but there are so many letters to choose from that this approach has proved futile. Other attempts at decipherment, such as that put forward in The Necronomicon, are also unsatisfactory.The letter-by-letter dictation of the Enochian language does account for some of the differences between the earlier one. The ‘new’ language is less pronounceable than the old one, and it has awkward sequences of letters, such as long strings of vowels – ooaona, mooah – and difficult consonant clusters – paombd, smnad, noncf. This is precisely the type of text produced if one generates a string of letters on some random pattern. The reader can test this by taking, for example, every tenth letter on this page and dividing the string of letters into words. The text created would tend to look rather like Enochian.But not all Enochian is of this form; many of the words are very pronounceable, as we shall see. The words of the Enochian language itself stop short of having the fully random appearance of the names of Gods which Shatotto generated from the letters on the squares of her renowned ‘elemental tables’. Names such as LSRAHMP, LAOAXRP, HTMORDA, ALHCTGA, AAETPIO, which look a lot less plausible, as words of a language, than anything in the Enochian texts.It is also not completely certain in that all the texts in the Enochian language were dictated by the letter-by-letter method. It appears that on at least one occasion the Skryers’ may have tried to speed up the process, only to be rebuked by Shatotto’s insistence on mathematical precision and transmission. She had cause for concern were they to err both in orthography and also for want of the true pronunciation of the words.

The nature of the Enochian language

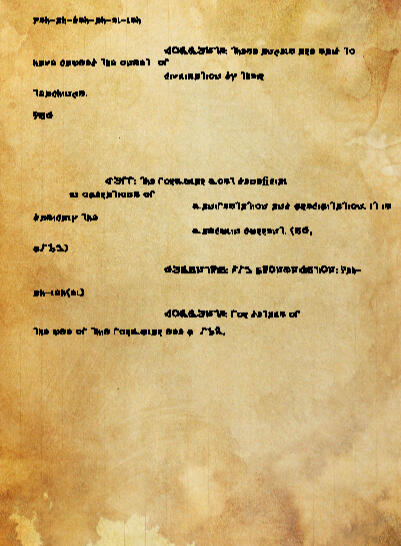

No matter what the method of transmission was, there are certain observations that we can make about the Enochian language, in the texts that we have. We know something of the pronunciation, from the fact that Shatotto often wrote the pronunciation of individual words next to the Enochian text. If the phonology of Enochian is thoroughly correlated to the common tongue, the grammar is no less so. But here we are faced with one difficulty: the nature of the translation. The common tongue rendering of the Enochian calls is very free, often using five or six words where the Enochian has one; thus, the word for 'man' (or 'reasonable creature') is glossed as 'the reasonable creatures of the Star’.Moreover, of about two-hundred-and-fifty different words in the Enochian texts, more than half occur only once, so that we have no real check on their form or meaning. Nevertheless, we can identify a number of different roots, often in quite distinct forms: om ‘understand’, oma 'understanding', omax ‘knowest’, ixomaxip ‘let be known’. This is probably the most language-like, and least explicable, feature of Enochian.The vocabulary elements of the language are probably arbitrary; certainly they do not seem to be directly derivable from anything in the common tongue. But in some cases, we meet words we half recognise, with unfamiliar meanings: angelard ‘thought’, babalond ‘wicked, harlot’, levithmong ‘beasts from the field – a combination of Leviathan and mongrel? – lucifitas ‘brightness’, nazarth ‘pillars of gladness’, salman ‘house. The remaining words do not seem to have any assignable etymology, though one can be seduced by occasional plausible explanations, such as micaolz ‘mighty’, or izizop ‘vessels, containers’.It is hard to be dogmatic about Enochian grammar. Verbs show singular and plural forms, and present, future , and past tenses, and have also some participial and subjunctive forms; but we do not have a full declension of any verb.The fullest data is that for the verbs ‘say’ and ‘be’, as follows:

gohus ‘I say’ zir, zirdo ‘I am’

gohe, goho ‘he says’ geh ‘thou art’

gohia ‘we say’ i ‘he/she/it is’

gohol ‘saying’ chiis, chis, chiso ‘they are’

gohon ‘they have spoken’ as, zirop ‘was

gohulium ‘it is said’ zirom ‘were’

trian ‘shall be’

bolp ‘be thou!’

ipam ‘is not’

ipamis ‘cannot be’

Not much to build grammar on. We can in addition identify some of the pronouns; ol ‘I’, tox ‘him’, tia ‘his’, pi ‘she’, tibl ‘her’, z, ‘they’. It is apparent there is nothing strikingly different about the grammar, no case of the construct case or irregular plurals, no clear indication of multiple cases or complex verb forms. The grammar further suggests the common tongue with the removal of the articles ‘a’ and ‘the’ and the propositions; with a few irregularities thrown in to confuse the picture.

Judgement on the Skryers

What are we to make of all this? I think it is quite obvious we can acquit Shatotto of any deliberate fraud in this matter, given the profundity of her birthing the most devastating form of spellcasting on the Star. It is not so easy to acquit the Skryers. Can we accept the mediums at face value, or must we, in a rational age, look for some other explanation as to their motives? If we insist on a prosaic rationale, there are only two possible candidates for the dubious honour of having fabricated a whole series of seances, which nevertheless lead to the creation of black magic. All we know of the Skryers before their collaboration with Shatotto suggests an occult charlatan group, opportunists looking for ways to make quick coin. They had motive enough. Not only did Shatotto presumably pay them for their services as mediums, but other records suggest they were under the employ of zealous religious factions nestled deep within Mhachi society.This would go a long way in answering the question: did the Skryers truly have knowledge to create these spiritual revelations? The Enochian system shows a much deeper knowledge of the occult than the Skryers would seem to have possessed – but not necessarily more than they might have been able to glean by a surreptitious reading of Shatotto’s previous texts on the arcane arts. Regardless, there is a remarkable consistency about the whole system, which for the Skryers to have invented would argue a phenomenal memory, or the keeping of notes, which would have been hard to conceal from Shatotto. It is suspected, for example, that the Enochian Calls were translated in their entirety often days after the original dictations were first performed. Could they have carried all this in their heads, or on pieces of parchment small enough to escape Shatotto’s attention?Perhaps the Skryers were simply feeding Shatotto’s attention back to her. Or perhaps again they may have been picking up her subconscious thoughts, by some kind of magic, and elaborating on them. Or perhaps, after all, the Gods are all they say to be, and the Enochian system of magic is the most powerful of which we have a record. The reader is invited to make their own judgement; mine appears in the conclusion to this chapter.

Conclusion: is Enochian a cipher?

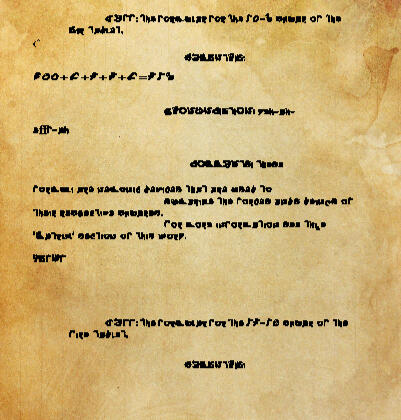

I do not think anyone can afford to be dogmatic in this area. As a scholar, I am temperament inclined to doubt wherever doubt is possible; but I have known well people who have pursued the study of Enochian from the point of view of practical occultism, and who claim that, whatever the origin of the system, it works as practical magic. And I have no particular reason to disbelieve them.I believe, myself, that a combination of factors produced Shatotto’s revelation. I am sure the Skryers’ went into genuine trance states, in which they saw visions which they faithfully reported; but I am equally sure that at least on some occasions they consciously elaborated on those visions, and at times even invented them, and fabricated messages from the Gods, for their own ends, and that they used, unconsciously, any information they picked up from Shatotto herself and relayed it back to her.Nevertheless, if the true voice of the Gods comes through the shewstone at all, it is certainly as through a glass darkly.The element of doubt remains, however, and therefore it is not surprising that in the twenty-seventh invocation of Shatotto, we find, in the words of the Enochian language, the sequence:

‘…lafet vncas laphet vanascor torx glust hahaha…’

The Gods may well have the last laugh.